The Science of Art

The Science Behind Those Sunsets You Can't Stop Instagramming

This was the first piece for a series seeking to explore artistic media and phenomena from a scientific standpoint, written for UC Santa Barbara students in Isla Vista, a beachside community with particularly beautiful sunsets.

Picture the scene: It’s 5:22 PM, it’s basically freezing at 60°F, and winter quarter midterms are looming just around the corner—but you’re not even mad, because damn, look at that sunset. You think you’ll be the artistic spirit in your friend group and post that unadulterated, organic, #nofilter Instagram. You take out your phone and see 13 Snapchat notifications. You already know you missed your opportunity but assure yourself that 24 hours and 1 minute from now you’ll have another chance to get those sweet, sweet Instagram likes. You grab another beer, watch the sun dip below the oil rig and, if you’re anything like me, wonder what the hell just happened in the sky.

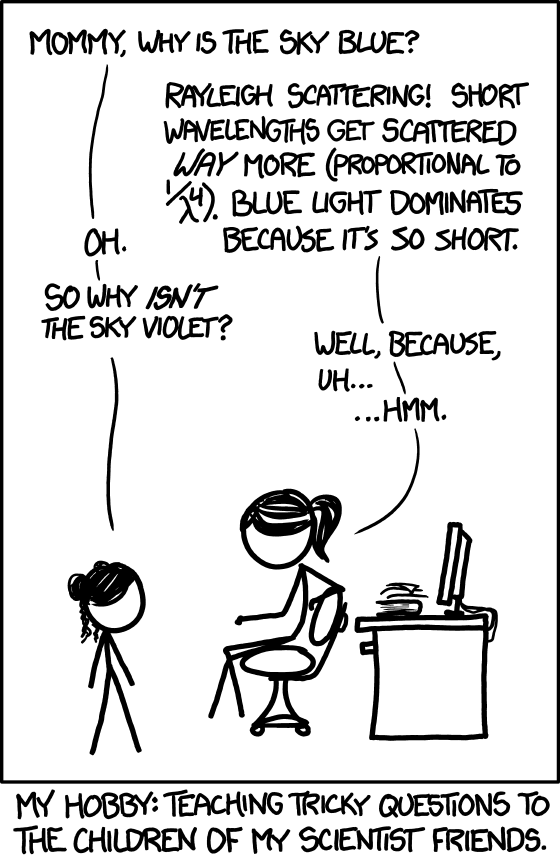

Okay, so why are sunsets, as routine as they are, so captivating? Why are Isla Vistans blessed with such Instagrammable skies every night? The answer lies in a phenomenon discovered by 19th century British physicist, Lord Rayleigh, called “Rayleigh scattering.” This is the scattering of light by small molecules or individual atoms such as air molecules. Particles effectively scatter light when they are much smaller compared to the incoming wavelengths of light. This is the key to the colors of the sky: air molecules are small enough to scatter sunlight, but not all light is created equally.

Sunlight consists of a spectrum of colors, ranging from violets and blues to oranges and reds—yeah, like that Pink Floyd album cover you have on your wall. Violet light has the shortest wavelengths and therefore interacts with small nitrogen and oxygen air molecules the most. In fact, violet light gets scattered much more than blue light but the cones in our eyes are not very sensitive to violet light. This is because sensitivity peaks at the middle, or green, part of the spectrum, which is closer to blue than purple.

If that were not the case, the sky would appear violet. So now we know why the sky is blue—but if a child asks maybe you shouldn’t respond with, “Because your eyes are lying to you.”

You’re probably wondering about now when I’m going to actually talk about sunsets. Well, the same concept applies wherever the sun is during the day, but where it is also makes all the difference. During the afternoon, when the sun is directly above, sunlight travels the shortest distance through the atmosphere before reaching your eyes. At sunrise or sunset, however, it travels a much greater distance. As a result, more violet and blue light is scattered and the light appears orange and red by the time it reaches your phone’s camera... I mean your eyes. Don’t worry, though—no light was harmed in the process of making your sunset. All of that scattered blue and violet light that didn’t reach your eyes is busy creating a blue sky in another timezone.

Now we’re getting somewhere—but we’ve only answered how the sky changes throughout the day, not on a day-to-day basis. Many factors contribute to the nuances of the evening sky and, of course, the quality of your #nofilter Instagram.

One of the most important factors of sunset color happens to also be one of the hardest to understand: Smog1. Smog consists mostly of aerosols3, which can be natural, resulting from volcanic eruptions and forest fires, or artificial, resulting from factories and exhaust fumes. Here’s where it gets confusing: they all do different things, depending on their size and uniformity.

Natural events like volcanic eruptions release aerosols that are mostly uniform, scattering the same wavelengths of light. Volcanoes can actually produce beautiful sunsets from the release of certain particles that tend to scatter more yellow light, leaving a vivid red sky. In fact, the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, and subsequent release of these aerosols, was thought to have inspired Edvard Munch’s famous painting, The Scream. All that being said, man-made pollution consists of many different types of particles that all differ greatly in size. As a result, all wavelengths of light are scattered, resulting in hazy, gray skies. So if a good sunset photo is what you’re looking for, you’re probably better off in a forest fire during a volcanic eruption than in Los Angeles. Isla Vista works just great, too.

Let’s go over some other factors that in influence sunsets, starting with seasons. Yes, the time of year does make a difference. Fall and winter tend to have brighter sunsets due to the dryer and cleaner air in the path of the sunlight. It’s no surprise I asked you to picture the opening scene during winter (In fact, on January 25, 2021, around winter quarter midterms, the sun will set at 5:22 PM).

Weather can also predict sunsets, to a certain degree. For example, departing storm clouds can often be slanted, which project down captured orange and red light. In addition, storms can wash away larger particles, resulting in cleaner air just like the seasonal effect during the fall and winter. So for all you sailors4 out there, the phrase “red sky at night, sailor’s delight; red sky in the morning, sailors take warning” is true. The red sky suggests clear air off to the west, moving towards you for the following day.

It’s probably no surprise to anyone that clouds can make for an extraordinary sunset—but like most other natural phenomena, all clouds are not created equal. Cloud water droplets are much larger than incoming light rays, so selective Rayleigh scattering does not occur. Rather, they scatter light without much color variation, projecting incoming light waves down below. To produce these vivid colors, however, clouds need to be high enough to intercept the sunlight before it loses color by passing through the atmosphere. Sometimes low-lying clouds can have the same effect but that usually means the atmosphere is very clean and transparent, which usually happens in the tropics or over the open ocean. Isla Vistans know a little something about this phenomenon.

All external factors aside, though, the real deciding factor for a beautiful sunset lies in our own perception. Just like looking at art in a gallery, perceiving our skies is quite the subjective experience. Even if all humans had the same opinions, no one sees color the same way. Remember how I said our cones are not sensitive to violet light? That applies generally to all humans, but our cones are most sensitive at slightly different wavelengths of light. This slight shift in peak sensitivity results in all of us seeing the world in a different light, quite literally. In fact, there are more unique frequencies of color in a rainbow than stars in the universe5 but our eyes can only make out about one million of them. We all see the world differently, but no one can even come close to seeing the entire thing.

⁘ ⁘ ⁘

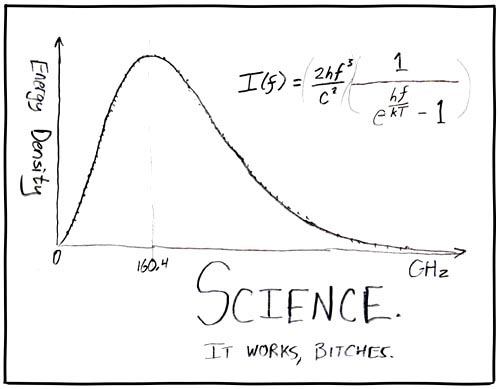

Back to the scene: the sun dips below the oil rig, and you take out your phone. You look at photos posted by your friends. Maybe they’re better than yours; maybe they’re just more timely. But no one else in the world had the same experience you just had. No one else perceived the same color, had the same feelings or considered the same mysteries behind such a routine occurrence.6 As Carl Sagan said, “It does no harm to the romance of the sunset to know a little bit about it.” From the spherical ball of hot plasma7 93 million miles away to the cones in your eyes, light makes a long journey8 to show us that science and art naturally reside together.

Footnotes

- Portmanteau2 of the words smoke and fog ↑

- Linguistic combination of multiple words or their sounds ↑

- Solid or liquid particles in the air ↑

- Rafters ↑

- To put it in an IV perspective: there are more stars in the universe than grains of sand on Earth. ↑

- Mostly because no one else probably read this article. You’re already winning in my book. ↑

- The sun ↑

- The length of “Touch” by Daft Punk (8:19) ↑